Native English speakers enjoy a great privilege. English is the language of medicine, science, aviation and many other fields. Thus, practically every nation includes English language lessons in their schools' core curriculum. Almost everywhere you go, speakers of other languages (should) have no problem understanding you.

On the one hand, that's great. We English speakers don't have to learn other languages. On the other, not learning how to speak other tongues deprives us of bilingualism's many benefits. It also makes us perpetual outsiders.

Language is integral to culture. If you don't know the language of the country you're in, you can only get a vague idea of how its society works.

To immerse yourself in your Chinese Experience, you must know essential Mandarin words and phrases. Not just how to say them but their impact and significance. You must know:

- the right way to greet and say 'thank you' in every situation

- how to show respect and affection

- how and why Chinese mannerisms and expressions came to be

- how to develop cultural competence

As 外国人 (wàiguó rén) - a foreigner, your appearance sets you apart even before you say your first 你好 (nǐ hǎo) - hello. However, you can find your path to acceptance into Chinese society when you prove how well you know its culture.

Unveiling the Essentials: Hello, Thank You, and I Love You in Mandarin

These three phrases are universal; they're also among the first you learn in any language class. You might not get lessons on love-speak right away but you'll certainly learn how to greet someone and thank them.

The only trouble is, you only get those Mandarin words' standard versions in your language classes. You might think Chinese native speakers use them the same way we do. But Chinese culture has vastly different norms for thanking people.

We say 'thank you' for everything; it's almost a reflex. By contrast, Chinese culture does not mandate thanks at every turn. This makes thanking someone more meaningful. It also calls for the right 谢谢 (xièxiè) - 'thank you' for each occasion.

Likewise with greetings. 'Hello!' is our default; we greet everyone from government officials to newsagents that way. We even preface every phone call with 'Hello'.

That's not the way to greet people in China, at least not if you're intent on demonstrating cultural competence. The standard 你好 only applies to certain situations. For more personal connections, you have to use the right greeting in its proper form.

What about expressing love? You must have a well-trained cultural eye to spot signs of love in China. You'll find few overt displays of physical affection - nobody holding hands or kissing in public. Outside of films and songs, you'll seldom hear 我爱你 (wǒ ài nǐ) - 'I love you'.

Don't get the idea that there's no love in China, though. Or gratitude or common courtesy. You'll find plenty of each if you know what to look for. Let's examine these three social essentials in the Chinese cultural context.

A Closer Look at Nǐ hǎo, Xièxiè, and Wǒ ài nǐ

As mentioned above, 你好 (nǐ hǎo) is Mandarin's generic hello. As a foreigner in China, nobody will expect you to go beyond that. You will impress native Chinese speakers if you know the right greeting for every occasion.

Delivering the right greeting is challenging but so is determining the right degree of thanks. In our culture, it's fine to lob the same 'thanks' to our mates, our mums and our teachers. But in China, each 'thank you' has its cultural weight and each implies a degree of reciprocity.

Our overuse of 'thanks' has made the word clichéd whether said sincerely or by rote. Still, our norms demand this show of gratitude in all cases. We don't even have to be specific about what we're thankful for.

In China, unless you're thanking a good friend, you must include the deed you're grateful for. If someone helps you with something, you should tell them 谢谢你的帮忙 (xièxiè nǐ de bāngmáng) - 'Thank you for your help'.

However, to thank your boss, you only need to use the formal 'you' ( 您 - nín) with a more emphatic thanks. Such an expression of gratitude is 感谢您 (gǎnxiè nín), preferably said as you make the hand gesture for respect.

As specific as greetings and thanks-givings are in Chinese culture, talk of love is indirect. Often, 'like' (喜欢 - xǐhuān) takes precedence over love whether you're discussing a person, idea or thing. Love is most often discussed as (爱情 - àiqíng), which represents love as a state, condition or mood, not a feeling.

Chinese people will speak of 爱情 in neutral terms but that doesn't mean they have no passion. Indeed, today's Chinese lovers have devised many clever ways to express their devotion to one another.

Cultural Insights Behind Common Mandarin Expressions

In China, love matches seem sterile at first glance. You'll see few overt signs of partnership or physical attraction, if any.

Historically, Chinese families made marriage matches based on several criteria. Those included auspicious dates and zodiac animal sign compatibility.

This practice continues today. Couples whose zodiac animals mesh well will receive their parents' blessings for marriage. They may rush to wed in the eighth month of a 'dragon year' because the number eight and the Year of the Dragon are both auspicious.

Couples still marry if their zodiacs are incompatible, of course. But they often do so against their families' wishes. One wedding I attended including a sobbing mother who was dead set against the union.

Unlike our marriages throughout history, Chinese matches don't necessarily hinge on money or business. However, the groom should have enough money to provide for his family. Even today, a house, a car and a job are marriage prerequisites for Chinese bridal families. The question of love seldom comes up.

Unlike our individualistic culture, Chinese culture is collectivistic. The self takes second place, which compels Chinese people to shy away from speaking in the first person. Rather than say 我爱你, you'll more likely hear 想你 (xiǎng nǐ) - 'want you', leaving the 'I' off. This serves as a reminder to you not to start many sentences with 我 lest you give the impression you matter the most.

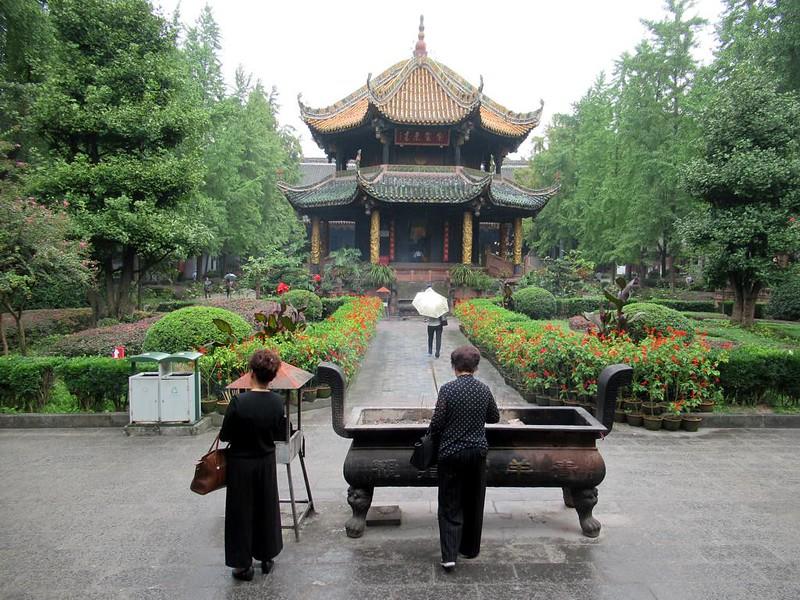

Chinese society is also hierarchical. China hasn't counted eras in dynasties for over 100 years, but it's difficult to forget 5000 years of history. Social ranking matters in today's Chinese culture and showing deference is important.

China reveres its senior citizens; this society also instils respect for authority. Such positions include teachers, politicians and bosses at work. Students treat even their dorm and class monitors with deference even though they too are students.

In all cases save the student monitors, you should show your respect by addressing such people with the formal 您 (nín) rather than 你 (nǐ). You write this character by placing 你 atop the heart pictogram (心 - xīn). Thinking of it as 'You have my heart' is a good way to remember whom to revere.

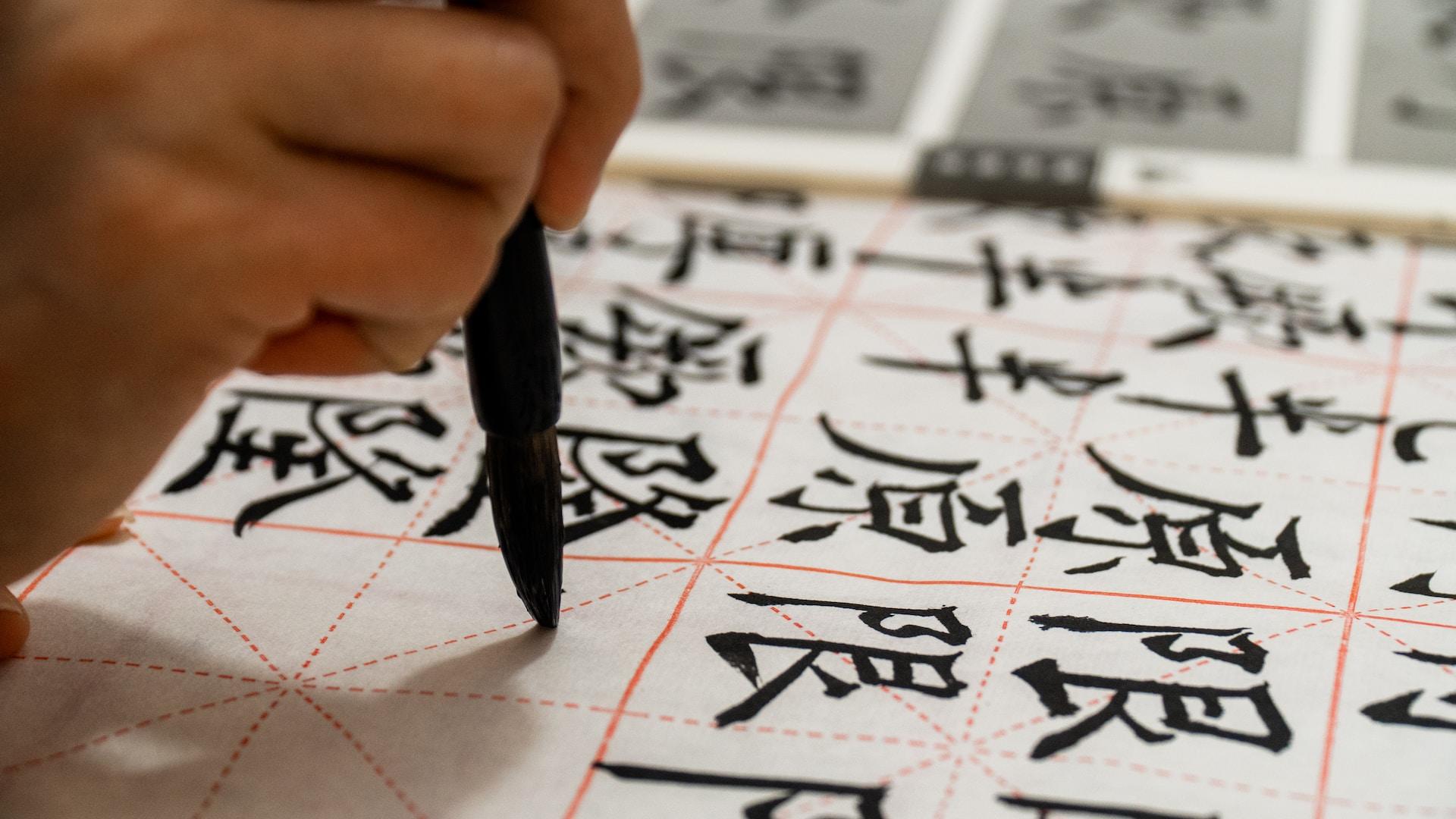

We can deconstruct 谢谢 the same way. It starts with the modified 'speak' radical (言 - yán) and then presents the 'body' character (身 - shēn), which also means 'morality, conduct'. The last character is a unit of length - 寸 (cùn - inch).

The Chinese 'thank you' is one of the more complex characters to write. Its difficulty level mirrors the depth of 'speaking morally for a length', which is so important in this culture. When you thank someone in Chinese, you're going beyond tossing out a kind word. At least in spirit, you're showing your moral stance.

Practice and Pronunciation Tips

Mandarin is a tonal language with roughly 400 sounds. Chinese speakers modify each one with their four tones, yielding about 1600 different syllables. Or 2000, if you count the neutral or 'zero' tone.

Of all the tones, the third is the hardest to pronounce. It is a falling-rising tone; pinyin marks with a small 'v' over the vowel. nǐ, wǒ and hǎo are all examples of such.

To master the third tone, dip your chin down and then raise it while speaking the syllable. If you learnt the hand gesture in your Mandarin class, it might help you do it as you practise speaking this tone. If you've not seen this gesture: bring your hand down and back up, tracing a 'v' form.

Using the right tone for the meaning you want to convey is one of the hardest parts of mastering Mandarin speaking. For instance, you might be out shopping for drinking glasses and ask for 'bèizi' (被子) instead of 'bēizi' (杯子). Don't be surprised if the clerk shows you quilts instead of cups.

Native Chinese speakers often clarify their meaning if there's a chance they might be misunderstood. For instance, someone introduces themselves as "我叫乐思" (wǒ jiào lè sī) - 'I'm called Le Si'. They would then specify "The 'Le' meaning 'happy' and the 'Si' from ‘thought’" (快乐的乐,思考的思 - kuàilè de lè, sīkǎo de sī).

Unfortunately, there are no shortcuts to perfect tone usage. Practice is the only way to improve your Mandarin pronunciation. Don't berate yourself for relying on pinyin until you get to the intermediate learning stage. Only then will you have a sizable collection of words in Mandarin with their proper tones to say what you mean.

Summarise with AI: