Life in Edo Japan was rich and brutal, in equal measure. How one's life went depended on which layer of the social hierarchy they operated on. Nobility, samurai families, and government officials lived well. The peasantry, made up of merchants, artisans, and those doing unpleasant tasks, had the hardest lives. The Tokugawa shogunate oversaw them all.

Shogunate Government: Hierarchy and Structure

The Tokugawa shogunate wrested power from the Ashikaga clan, following the Battle of Sekigahara (October 1600).

The template for shogun rule had been laid nearly 700 years before, but the Tokugawa clan had ideas on what to do differently.

As established under Japan's first shogunate, the emperor would remain the country's figurehead and spiritual leader. The shogun, the military ruler, had all the political and economic power - at least, officially. He was the functioning head of government.

As the lead politician, the shogun had to mind his noblemen's concerns. Those diamyo had no political power, but often swayed the shogun to their cause. In fact, it was often in his interest to comply with them. The samurai - the Japanese warrior class, helped maintain this structure, and enforce diamyos' positions.

Japan's system of military government.

This is the system that the samurai helped enforce.

Beneath the samurai, the peasant class filled the next rung on the hierarchical ladder. This social class comprised 90-95% of the population, made up of farmers, artisans, and buraku - those who took on the most undesirable tasks.

Moving the Capital

The Tokugawa shogunate planned to unite the diamyos' holdings under a central government. Declaring Edo the country's seat of power was among the most radical moves the Tokugawa shogunate made. Until then, Kyoto had been the country's capital.

It wasn't a 'moving the capital' operation.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was an important diamyo. He instructed the shogun to set his base in Edo.

It was far away from Japan's trading partners, Korea and China. It was hard to get to, and inhospitable, at first. But, as the country flourished, Edo grew into one of the world's largest population centres. This move, and the later re-opening of the country to foreigners, led to the modernisation of Japan.

The Tokugawa Shogunate Unites Japan

Diamyos informally ruled Medieval Japan. These powerful, hereditary leaders controlled large areas, called han. The hierarchy dictated that diamyos were technically under the shogun’s authority. However, those lords managed their territories independently, collecting taxes, and controlling infrastructure and military forces.

As you might imagine, this piecemeal approach to government made it hard for the shogunate to rule over all the land. The military government - bakufu, implemented a list of policies to limit the diamyos' power and independence.

The shogun oversaw the central government in Edo.

The diamyos gave their loyalty to the shogun, and ruled their han according to shogun policy.

The shogunate timeline is long, stretching nearly 700 years. Three clans attempted Japan's unification over that time, with the Tokugawa finally succeeding. With everyone on the same page, Japan entered a relatively peaceful, prosperous time.

Sakoku: Japan Isolates Itself

In Europe, the Enlightenment spurred thinkers to dizzying intellectual heights. That boom resulted in new technologies, including seaworthy vessels that could travel unimaginable distances. At the same time, religious fervour reached new peaks, carrying missionaries to distant lands, to convert indigenous populations.

All this happened during the Tokugawa shogunate. Foreign intellectuals, and religious leaders, made inroads into Japanese society. Their activity destabilised Japan's social harmony. Removing their presence, and instilling isolation (sakoku), seemed to be the only solution.

The shogun adopted this policy to bring about political stability.

Trouble was, the dyamio had trade relations of their own. They too contributed to the country's growing instability. However, this trade boosted the country's economy, and brought in new technology. The shogun realised he could not isolate Japan completely, so he allowed four 'access points' for trade:

- Nagasaki: Chinese trade Dutch East India Company

- Hokkaido: trade with Aizu people

- Tsushima Island: trade with Korea

- Ryūkyū Kingdom for general trade.

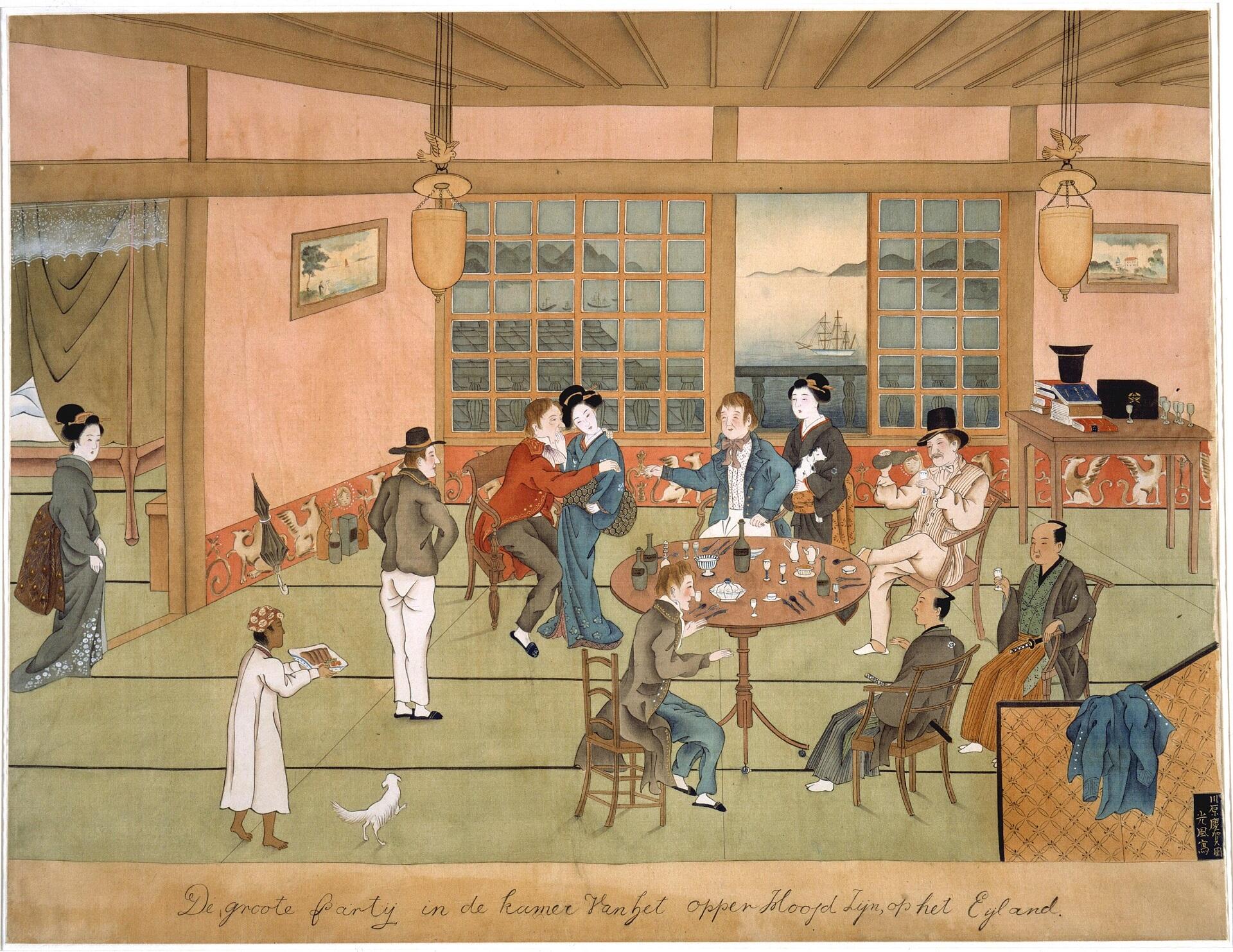

Foreign trade, out of Nagasaki, took place on an island, apart from the city. Foreigners were not allowed entry to the town, and townspeople could not step foot on the island without special permission. This edict was militarily enforced.

Japan did not close itself off all at once. Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun, initiated sakoku in1635, and gradually limited outside access. Sakoku ended in 1853, as Captain Matthew Perry threatened military action to force Japan's re-opening.

The Impacts of Isolation

Like every initiative, sakoku had its good and bad points:

Beneficial aspects

- cultural development and preservation

- flourishing of art

- 'pure' intellectual pursuits

- avoiding cultural influence

Harmful aspects

- minimal technological advances

- loss of science gains

- limited access to resources and raw materials

- constant external assaults

Preserving the Japanese way of life was a double-edged sword. On one hand, culture, religion, and social structures remained untouched. On the other, progress and innovation were limited, but not in every aspect of Japanese life.

Edo Period Japan: Life and Culture in Edo

With the relative peace and convenience of urban living, people soon craved activities to capture their attention. Thus, Edo Japan became a hub of culture. There, people debuted new forms of literature - the haiku, and link-versed novels. Other forms of entertainment, dancing, music and theatre found eager markets, too.

Kabuki got its start during the Edo period. For those unwilling to sit through exaggerated dance moves, a second form of theatre emerged. Bunraku was kabuki, but performed with puppets, not human actors.

As warriors were barred from attending theatre performances, many disguised themselves before taking their place in the audience.

New technologies emerged to make leisure even richer. Improved woodblock printing allowed fans to own the likeness of their favourite kabuki stars - or, their favourite courtesans. Owning illustrated books, and drawn, coloured images of the countryside, became status symbols, too.

Life for Women during Edo Period Japan

Culturally-rich Edo offered women a chance to strike out on their own, if only in a limited capacity. The shogunate made provisions for females to entertain, as long as they kept to their designated yūkaku (the city's pleasure quarters). These women were geisha forerunners: they didn't entertain so much as deliver carnal pleasure.

Women also entered the theatre as performers. Historians credit one such woman, Izumo no Okuni (pictured), as the inspiration for kabuki theatre.

Otherwise, as in the past, women had few rights or prospects. Peasant women had only a life of hardship to look forward to. Women from wealthy families could expect a rich, protected life, in part because they were trained to protect themselves.

Females from samurai and noble families spent much of their girlhood mastering the martial arts, and learning how to use weapons for self-defence. They carried kaiken, a type of dagger, for fighting in close quarters - and, to commit ritual suicide (sepuku), if needed. Some of these women became samurai, though they never received official recognition.

Edo and the Economic Boom

With the country united and (mostly) politically stable, Japan had the space and means to grow economically. Initially, much of this growth came from foreign commerce. However, after the country embraced sakoku, domestic initiatives ruled.

Construction, housing (as pictured above), commercial zones, and infrastructure made it easier to trade. Banking facilities began to dot the landscape, giving people safe storage spaces for their wealth. Merchants especially benefited from the banks, as they could secure capital to invest in their business.

As esteem grew for the formerly reviled merchants, those worthies formed associations. Their activities included lobbying the government to support the agricultural sector, giving them more product to sell. They also enlisted artisans to produce novelties for well-to-do urbanites to indulge themselves with.

The Merchant Class in Edo Japan

Traditionally, the merchants occupied the lowest rung in Feudal Japan hierarchy. However, new economic ideas changed long-held views about merchants. They paid taxes, thus contributing to society. They were, in fact, the commercial engine of Edo Japan, so their social status rose accordingly.

Feudal Japan hierarchy, the country's social structure, was rigid. Despite that, life under the shoguns was stable and progressive, particularly during the Tokugawa shogunate. The majority of the population (the peasant class) only squeezed out a living, and natural disasters set them back further, still. That, as many in the city enjoyed ukiy-o culture - the urban lifestyle.

The city's growing middle class had money and time to spare, so they sought pleasure in Edo's brothels, shops, and eateries.

It all came to an end in 1868, towards the end of the Boshin War. Though a privileged class, the daimyo wanted more autonomy and a more active role in politics. A group of them aligned themselves with the emperor, stripping the shogunate of power. And so, the era of Edo Japan came to its end.

Summarise with AI: