GCSEs are no joke, seeing as your results may determine your future. And, of all the GCSEs you may opt to take, three subjects are non-negotiable: English, Maths and Science. If your marks aren't high enough... well, you already know what happens next.

Unfortunately, two of those subjects, Maths and Science, prove the most daunting. Even if you've chosen Biology as a single-science exam, there's still much you have to know about.

For instance, if you're sitting in AQA Biology, you have to know about cellular respiration, photosynthesis, and how various organisms maintain homeostasis. How they get nutrition and how nutrients and waste are transported and expelled.

Superprof turns the spotlight on selected topics that you'll see on your exam papers and presents them in a different - hopefully more expanded and easily digestible light. No pun intended.

Find biology tutors near me here on Superprof.

Plant and Animal Nutrition

To grow and maintain homeostasis - the state of being healthy and functioning, all organisms need nutrition. The way they secure nutrition is as varied as the species themselves.

The first thing to know is that practically every living organism falls into one of two categories: heterotrophs or autotrophs.

Find a biology tutor here on Superprof.

Autotrophs make their food out of environmental components: carbon dioxide, water, light and the chlorophyll in their bodies. Light energy is converted to chemical energy which acts on the water molecules, splitting them into their component part - hydrogen and oxygen. The carbon dioxide molecules are also reconfigured, with the end result being sugar, which the plant uses as food. Water and oxygen, the process's waste products, are expelled.

As long as autotrophs - plants and certain bacteria have light exposure and their chlorophyll remains undamaged, they will continue to produce food for themselves, and water and oxygen for the environment.

Heterotrophs get their nutrition from other organisms; they are consumers of other organisms. Autotrophs, by contrast, are producers.

How heterotrophs secure their food depends on what type of organism they are. They may be holozoic, saprophytic or parasitic.

Even if you've not seen the South Korean hit film, Parasite, you likely know what parasites are, so let's talk about how they secure nutrition. They attach themselves to their host, often causing them harm, and feed off of them by capturing nutrition that was meant to maintain the host's homeostasis.

If you have a furry pet, you're probably vigilant about protecting them from fleas and ticks. These parasites feed off their hosts' nutrient-rich blood; in the process, they may even pass on a disease.

Other parasites, such as tapeworms, are internal; they're often accidentally ingested without the organism knowing they are consuming something that could harm them. Plants, too, may be parasitic, especially non-native, invasive species that choke native plants. Some types of vines qualify as parasitic.

Even though such vines may produce their own food through photosynthesis, they also feed off their host plant - trees or other hardy species. That qualifies them as mixotrophs.

What's a mixotroph? To find out more about the different types of producers and consumers, you need our full-length article.

Enzymes

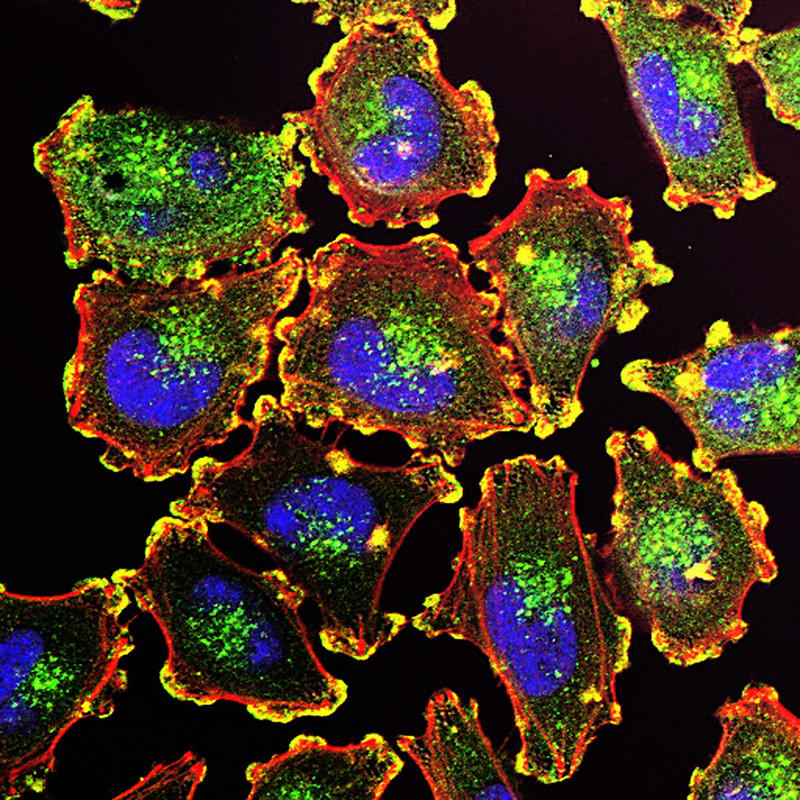

Enzymes play a huge role in how consumer organisms process food. In the last segment, we mentioned holozoic and saprophytic heterotrophs; those classifications have everything to do with enzymes.

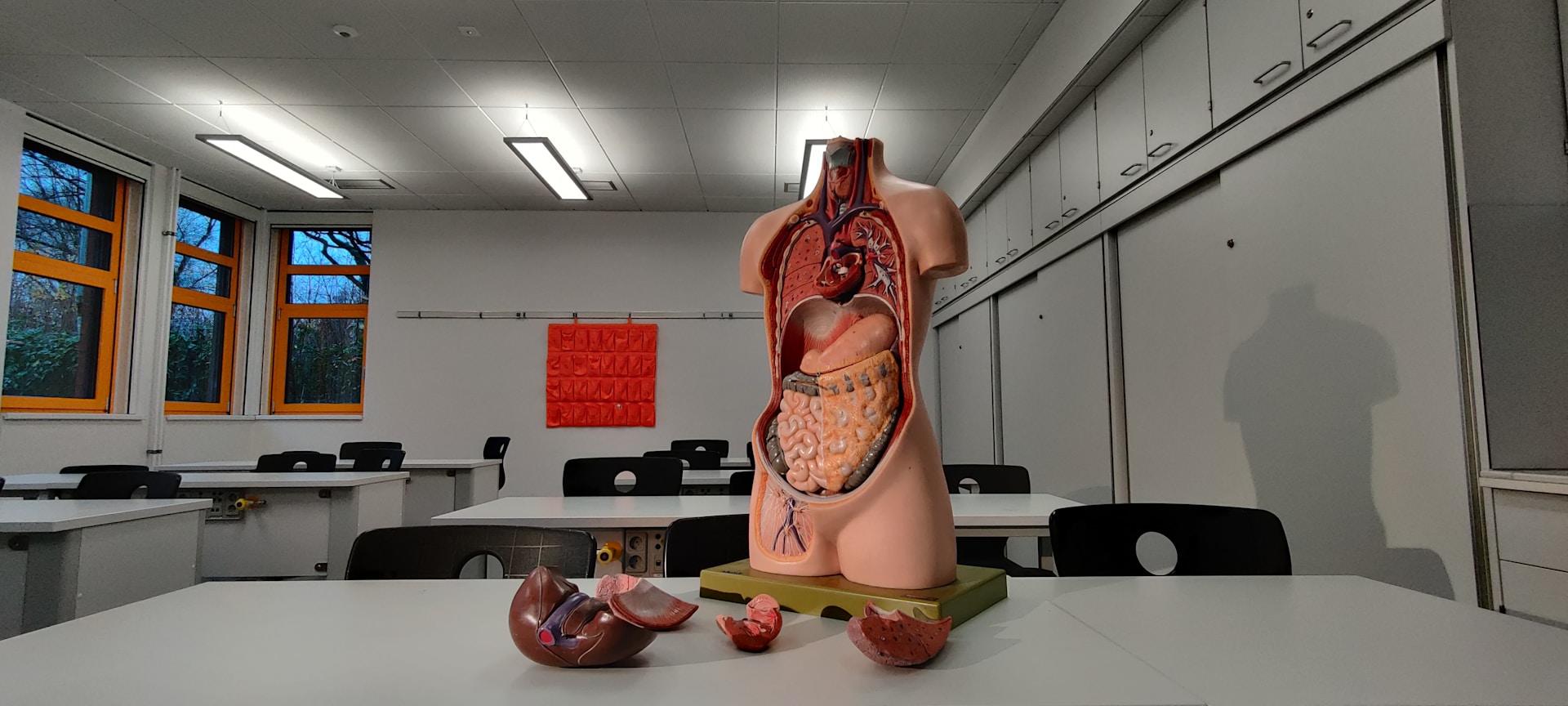

Holozoic heterotrophs' enzymes are found in various parts of their bodies - the stomach, the intestines, the mouth and so on. When such organisms consume food, the enzymes get to work, breaking molecules down into component parts that are small enough to pass through red blood cell walls.

Most mammals, including humans, and some microorganisms are holozoic.

Opposite of the holozoic nutrition model are the saprotrophs and saprophytes; organisms that disgorge enzymes onto their food and wait for them to break the food down into suitable particles. The common housefly is a good example of an organism that gets its nutrients through saprotrophic consumption. Flies disgorge enzyme-laden saliva onto their food, allowing it to decompose before consuming it.

With the assistance of a biology tutor, students can overcome learning obstacles and reach their full potential.

Fungi are an example of saprophytes; they feed and grow on decayed or dead organic matter.

Regardless of whether the organism is a saprotroph or saprophyte - animal or vegetable, enzymes do all of the heavy liftings in processing food for nutrition.

Enzymes are specially-shaped proteins, each designed to unlock a specific nutritional component: proteins, lipids, carbohydrates and, in ruminants, cellulose. This concept is explained with the lock-and-key hypothesis, which essentially postulates that enzymes are shaped to work on specific types of molecules.

The enzyme protease unlocks proteins; breaking them down into amino acids. Carbohydrase works on starches and complex sugars - polysaccharides and disaccharides, turning them into simple sugars that are stored for energy. Lipase breaks down the lipids we take in, extracting minerals, glycerol and other valuable molecules vital to nutrition.

As with so much else in biology, there's much more to enzymes than any short snippet can provide. You need to get the whole story on them; from where they're produced to how they're built and how they work.

Transport in Plants and Animals

Understanding how organisms find or create food is one thing; understanding how those nutritional molecules get where they need to be to maintain homeostasis is another topic altogether. So important is this topic that your GCSE Biology exam has an entire section devoted to testing your knowledge about it.

Every living organism needs food, water and oxygen to live and grow, and they all travel along the same pathways - but have different uses.

In plants and some bacteria, most of the oxygen taken in from carbon dioxide and water molecules becomes a waste product of the photosynthesis process. Still, some oxygen is needed to form the sugars that will feed these organisms; the unused oxygen will be expelled from the organism.

Plants' transport systems can be compared to a two-lane highway, with one half called the xylem and the other, the phloem. They are wrapped into vascular bundles, with the xylem forming the core and the phloem surrounding it.

Xylem works much like a drinking straw. It is made up of non-living cells that transfer water and minerals in one direction only: from the plants' roots to its furthest extremities. The flow of water through the xylem is regulated by the stomata opening and closing.

The stomata are found on the leaves' undersides; they are pores that release oxygen and excess water from the plant. As they release those substances, a vacuum is formed; water then advances to fill the space left by the ejected substance.

By contrast, the phloem is made of living cells; it transports stored nutrition from the leaves - where it is produced to every part of the plant calling for it. Whereas transport in the xylem is driven by a system of negative pressure (vacuum or tension), the phloem operates on a system of hydrostatic pressure called translocation.

In animals, transport is a bit more complex but still consists of two systems: the circulatory and the excretory.

The circulatory system is made up of blood vessels and blood; the heart drives this closed-loop system. As the blood is pumped through the body along its vascular path, it delivers nutrients and oxygen throughout. By the time blood passes through the capillary system - from the arteries to the veins, it has spent all of its load and is now ready to pick up carbon dioxide, which will be exchanged in the lungs and, ultimately, expelled.

Excretory systems are also comparable from plants to animals, even if animals' systems are far more complex, they operate on the same principles.

Understanding the similarities - and the differences between plants' and animals' transport calls for a systematic comparison of the two.

Gas exchange and Respiration

The most important fact you need to remember regarding respiration is that it does not necessarily represent breathing - pulling air into lungs and expelling it, although the concept is similar. Breathing, as commonly defined, means 'ventilation'; the respiration your GCSE Biology exam refers to is converting food to energy.

Organisms may undertake this process aerobically or anaerobically. To simplify this explanation, let's imagine a marathon runner.

Throughout the event, the runner's muscles have enjoyed a steady supply of nutrients and oxygen, delivered by the blood flowing through their vascular system. The buildup of carbon dioxide those muscles have created, the waste product of the fuel they've burned, is carried away.

This example illustrates aerobic respiration.

Toward the end of the race, that runner may sprint toward the finish line, pushing themselves harder than their muscles can stand. Instead of burning oxygen, those muscles draw on glycogen stores for the extra energy needed to power the extra effort.

Not using any oxygen is the definition of anaerobic respiration.

Respiration in plants is an 'opposite' proposition. Remember that photosynthesis requires carbon dioxide and turns oxygen into a waste product - exactly the inverse of respiration in animals. Furthermore, as long as there is plenty of light, plants' net gas exchange - the amount of oxygen they expel versus the amount of carbon dioxide taken in, ensures the plant will produce more food than it expels gas.

Where and how do plants expel gas? That's the topic of a whole other article...

Summarise with AI: