If you are studying poetry, Shakespeare, or English literature at any level, you will inevitably have to grasp with this thing called the sonnet. But what exactly is a sonnet?

A sonnet is a 14-line poem written in iambic pentameter, traditionally exploring themes like love, time, or nature. It follows a specific rhyme scheme and structure, with popular types including the Petrarchan (Italian) and Shakespearean (English) sonnets. Sonnets often present an idea or problem in the beginning and a resolution or twist at the end.

Here is a brief overview of the main types of sonnets, which will be discussed in detail throughout the article:

| Type of Sonnet | Structure | Rhyme Scheme | Themes/Features | Famous Users |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petrarchan (Italian) | 14 lines: Octave (8) + Sestet (6) | Octave: ABBAABBA; Sestet: CDECDE or CDCDCD | Problem (octave) and resolution (sestet); strong thematic shift (volta) between parts | Francesco Petrarch, John Milton |

| Shakespearean (English) | 14 lines: 3 Quatrains + Couplet | ABAB CDCD EFEF GG | Explores themes through quatrains, with a final summarising twist in the couplet | William Shakespeare |

| Spenserian | 14 lines: 3 Quatrains + Couplet | ABAB BCBC CDCD EE | Interlocking rhyme scheme creates a flowing, continuous feel | Edmund Spenser |

| Miltonic | 14 lines: Similar to Petrarchan | Often ABBAABBA CDECDE | More flexible; uses enjambment and deeper philosophical or political themes | John Milton |

| Modern/Contemporary | 14 lines (variable structure) | Flexible or experimental | Often breaks traditional rules; used for modern themes and voices | Various 20th–21st century poets |

| Curtal Sonnet | 10½ lines (shortened form) | Variable (usually follows a Petrarchan pattern, compressed) | Condensed form of the Petrarchan sonnet | Gerard Manley Hopkins |

So, what is a Sonnet?

For those of you who have never before set foot into the world of literature, let's start from the very basics. A sonnet is a form of poetry. This means that the word refers to a range of different poems that share certain conventions of length, structure, style, and themes. These conventions are what make a sonnet a sonnet (and don't panic, as we outline these below).

The History of the Sonnet

What is super-important to remember in the study of literature is that poetic conventions are determined by history - meaning that you need to know the history of poetic forms if you are really going to understand what the poets are doing.

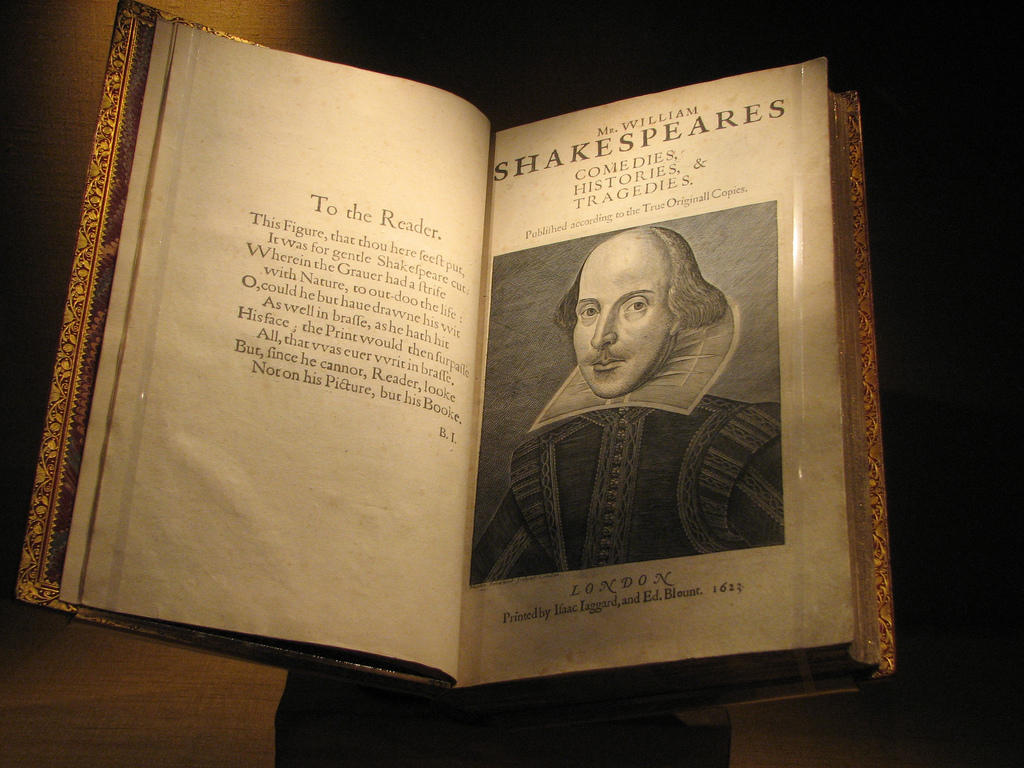

The sonnet is originally an Italian invention - and the word sonnet itself is derived from the Italian word “sonetto,” which means a “little song” or sound. Developed in Sicily by a bloke called Giacomo da Lentini in the thirteenth century, this little poetic form (whose conventions had not yet been formalised) inspired the greatest poets of the Italian Renaissance. These include Petrarch - about whom you'll hear much more - Dante, and Guido Cavalcanti.

Due to these poets' contemporary fame and prolific work, the sonnet became with them recognisable as it is today. And, from this point, people in England and France began to write sonnets too. Over the centuries, all of Europe started to write sonnets - and, in the English speaking world, after Shakespeare, some of the greatest sonnet-writers are to be found in the Romantic period at the turn of the nineteenth century (these include names like John Keats, William Wordsworth, and Percy Bysshe Shelley).

Poets are still writing sonnets today - but, these days, writers are more comfortable with playing with the once-strict structure of the form. We'll talk about this more below.

Why do Poets Write in the Sonnet Form?

Let it be said that the form has had enduring appeal among poets for a number of reasons. Firstly, the appeal of the form is due to its association with some of the biggest names in the history of literature: Shakespeare, Petrarch, Wordsworth. As you become more familiar with poetry, you will see that poets like to refer back to the ways that other poets had written in the past; the sonnet offers a great way to do this.

Find some fun poetry lessons on Superprof.

Secondly, the sonnet, given its brief length, is great for expressing a feeling, thought, or idea. The brevity facilitates the communication of a strength of feeling that can be lost in longer forms.

Thirdly, whilst the sonnet is traditionally known for focusing its attentions on the theme of love, the form allows for a great flexibility in its content. You will these days see sonnets written on everything from politics to war to ice cream. What makes this possible is the form's argumentative structure, which, as you will see below, is an essential part of the sonnet.

The Main Types of Sonnet

In the English-speaking world, we usually refer to three discrete types of sonnet: the Petrarchan, the Shakespearean, and the Spenserian:

- Petrarchan (Italian) Sonnet – Divided into an octave (8 lines) with an ABBAABBA rhyme scheme and a sestet (6 lines) with varied rhyme patterns (e.g., CDECDE). It typically presents a problem and a resolution.

- Shakespearean (English) Sonnet – Composed of three quatrains and a final couplet, with the rhyme scheme ABABCDCDEFEFGG. It often explores a theme and concludes with a twist or resolution in the couplet.

- Spenserian Sonnet – Similar to the Shakespearean but uses interlocking rhymes: ABABBCBCCDCDEE.

- Miltonic Sonnet - Used by John Milton, it breaks traditional rhyme and thematic rules, often featuring more complex ideas and a seamless flow between the octave and sestet

All of these maintain the features outlined above - fourteen lines, a volta, iambic pentameter - and they all three are written in sequences. The primary difference is the rhyme scheme.

We'll look at these three types of sonnet, and then finally consider some of those that don't really fit into the structure we have all been taught.

Petrarchan Sonnet

The first sonnet is the Petrarchan, or Italian, sonnet. Named after one of the form's greatest practitioners, the Italian poet Petrarch, the Petrarchan sonnet was the earliest strict sonnet form (he lived from 1304 to 1374).

As we noted above, the Petrarchan sonnet is divided into two stanzas: the octave (the first eight lines) followed by the answering sestet (the final six lines). Let's take a look at a Petrarchan sonnet, by the English poet William Wordsworth (as this is easier than reading medieval Italian!).

London, 1802

(A) Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour:

(B) England hath need of thee: she is a fen

(B) Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen,

(A) Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower,

(A) Have forfeited their ancient English dower

(B) Of inward happiness. We are selfish men;

(B) Oh! raise us up, return to us again;

(A) And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power.

(C) Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart:

(D) Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea:

(D) Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free,

(E) So didst thou travel on life's common way,

(C) In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart

(E) The lowliest duties on herself did lay.

So, here, in the first line, we've added markings to highlight the stress of the iambic pentameter (try it for yourself in the rest of the lines!).

And we've neatly highlighted the volta after the eighth line (do you see how the poem's tone changes - from a critique of England to a celebration of Milton?). In Petrarch, the volta usually separates the shift from an argument or question in the octave to a resolution in the sestet.

But what do those letters mean before each line? This is how we refer to rhyme scheme, in which A rhymes with A, B with B, and where each new sound requires a new letter. So, what do we have here? ABBAABBA, CDDECE.

The Petrarchan sonnet will almost always begin with that ABBAABBA octave. However, the rhyme scheme of the sestet can change - so watch out. Here, Wordsworth uses CDDECE, but the most common rhyme schemes in Petrarch are CDECDE or CDCDCD.

After the Petrarchan sonnet was first brought to England by Sir Thomas Wyatt, Henry Howard began translating and writing his own versions of Petrarch. His works were considered more faithful to the original than the work of his English counterparts. He made modifications to the Petrarchan sonnet which then became the structure of what we know as the Shakespearean sonnet.

This structure was established to better suit the English language which was somewhat lacking in the rhyming words that Italian boasts.

The Shakespearean Sonnet

The Shakespearean, or English sonnet, follows a different set of rules. Here, there are usually three quatrains and a couplet following a rhyme scheme like this: ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG. This is the primary difference between the Petrarchan and the Shakespearean sonnet. Let's take a look at Shakespeare's Sonnet 130:

(A) My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun;

(B) Coral is far more red, than her lips red:

(A) If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

(B) If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

(C) I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

(D) But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

(C) And in some perfumes is there more delight

(D) Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

(E) I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

(F) That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

(E) I grant I never saw a goddess go,

(F) My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

(G) And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare,

(G) As any she belied with false compare.

Much like in the Petrarchan sonnet, the Shakespearean sonnet contains a volta. There is a difference here, however. The volta can either come after the first eight lines or, as in Sonnet 130, at the beginning of the couplet. Here, it is used to signal a conclusion, explanation, or counterargument to the previous 3 stanzas.

In Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130 the first twelve lines focus on the speaker’s mistress, comparing her unfavourably to nature. But the final couplet changes the tone completely, that despite all of her flaws he does love her.

Shakespeare uses Sonnet 130 as a satire of other poets who compare their loves to nature’s beauty. In fact he takes it to the extreme nearly leaving the mistress completely unlovable!

The Spenserian Sonnet

A contemporary of Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser lived from 1552 to 1559. His sequence, Amoretti, was his main engagement with the sonnet form - and his other works included The Faerie Queene, an allegory about Elizabeth I, and The Shepherd's Calendar, a poem about shepherds, surprise surprise.

The Spenserian sonnet has a similar structure to a Shakespearean one, with three quatrains followed by a couplet. The interesting thing about the Spenserian sonnet is, of course, the rhyme scheme. Let's take a look at Spenser's Sonnet 75.

(A) One day I wrote her name upon the strand,

(B) But came the waves and washed it away:

(A) Again I write it with a second hand,

(B) But came the tide, and made my pains his prey.

(B) Vain man, said she, that doest in vain assay,

(C) A mortal thing so to immortalize,

(B) For I myself shall like to this decay,

(C) And eek my name be wiped out likewise.

(C) Not so, (quod I) let baser things devise

(D) To die in dust, but you shall live by fame:

(C) My verse, your virtues rare shall eternize,

(D) And in the heavens write your glorious name.

(E) Where whenas death shall all the world subdue,

(E) Our love shall live, and later life renew.

So, what do we have here? Remembering that Shakespearean sonnets follow the ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG form, the Spenserian sonnets are slightly different: ABAB, BCBC, CDCD, EE. So, the second rhyme of the first quatrain is taken to be the first of the second quatrain. Again, it ends with a couplet.

Where's the volta? Look at line nine, the first line of the final sestet. 'Not so', says Spenser, introducing a contradiction. As in Shakespeare, the volta either appears here or at the beginning of the final couplet.

The Most Important Features of a Sonnet

As we saw above, a sonnet is simply a poem written in a specific form. But to recognise a sonnet when you see one, you need to know the specific characteristics of that form. So, to summarise, here are the need-to-know features of a sonnet.

The Sonnet's Main Features

| Fourteen lines | Generally, all sonnets have fourteen lines. You will find some exceptions, but the poets will do this deliberately. |

|---|---|

| Volta | The fourteen lines are divided into two sections, usually of eight lines and six. The break between the two parts is known as the volta. |

| Iambic pentameter | This is what we call the metre of the poem: the number of syllables in each line of the poem. An 'iamb' is a set of two syllables, the first unstressed and the second stressed. 'Pentameter' shows that there are five of these 'iambs' in a line. So, you have ten syllables: unstressed, stressed; unstressed, stressed, etc. |

| Rhyme scheme | Different types of sonnets have different rhyme schemes, and some don't rhyme at all! You'll see more about this below. |

Let's Add a Little More Detail...

So, to flesh this about a bit, let's pay a bit more attention to each feature.

Lines and Structure

We've just noted that a sonnet has fourteen lines. But what you need to remember is that depending on the type of sonnet, these lines are arranged in different ways.

So, in a Petrarchan sonnet (we told you he'd come up again!), the lines are grouped into two: an octave (that means a group of eight lines) and a sestet (a group of six).

In Shakespearean sonnets and Spenserian sonnets, on the other hand, you have three quatrains (four lines) and a couplet (two lines). You'll find more on how these lines rhyme in the sections on each type of sonnet below.

The Volta

Whilst you will find a volta in many other forms of poetry, they are really quite important to the sonnet. What do we mean by the volta, then? In Italian, this word means 'turn' - and, in the sonnet, this is the moment at which a change occurs in the poem. This change might be in tone, argument, or thematic focus - but it is very rare to find a sonnet without one.

As we note above, these usually occur after the eighth line of the poem - for Petrarch, after the octave, whilst for Shakespeare and Spenser after the second quatrain. You'll notice this change quite easily, as they are usually signaled with a 'but', 'however', or 'and'.

Iambic Pentameter

This may look like a scary poetry word, but don't worry about it too much. Let's break it down.

'Metre' refers to the rhythmic structure of a line in poetry: how many syllables, how these are grouped together. 'Penta-' comes from the Greek word for 'five'. So, from 'pentameter' you know that the metre of a sonnet has something to do with five.

As we said above, the word 'iamb' refers to a group of two syllables, one unstressed and one stressed. There are five of these in each line when we talk about iambic pentameter. As all English literature teachers will tell you, the line will scan like this: dee-DAH dee-DAH dee-DAH dee-DAH dee-DAH.

To see this in action, look at this line from Shakespeare's famous Sonnet 18, in which we have highlighted the stressed syllables:

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Count the syllables in the line (there are ten!). Now, count the stressed syllables (there are five!).

But if we switch the stressed syllables with the unstressed ones, we can see how the line becomes a little clumsy:

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

The Sonnet Series

One of the main historical conventions of the sonnet is that they usually come in series. Think about Shakespeare's poem above. Why is it called 'Sonnet 18'? He didn't name it that. Rather, because he wrote 154 sonnets, each individual one is known by its number.

A lot of people have written sonnets in sequences. The most famous early sonneteers all wrote series: Philip Sidney's Astrophil and Stella; Shakespeare's Sonnets; Spenser's Amoretti. This convention has remained with us, as, in the twentieth century many other writers have composed sonnet sequences: Rainer Maria Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus, John Berryman's Sonnets.

These are the things that have developed the association of sonnets with the theme of love - as all of these sequences deal with a passionate speaker talking to a loved object.

Playing with the Form: Other Sonneteers

Whilst what we have just covered are the main historical types of sonnets, lots of poets have decided to take the basic structure of the form and change its content. Consequently, whilst these above are important to know, it is worth stressing that they are not the only forms of sonnets around.

Let's take a look at just a handful of different sonnets that play with the conventions of the form.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Sonnet

1. Find Inspiration

Whereas Shakespeare’s sonnets generally revolve around love, you could, in fact, choose any topic for your sonnet. You could even look to modern pop songs for inspiration!

Taylor Swift’s Shake It Off is a prime (and fun!) example of iambic pentameter usage in a modern context.

Other songs sung in iambic pentameter include:

- One Direction – History

- Alessia Cara – Here (a particularly good example as she gives each foot’s downbeat extra stress)

- Halsey – New Americana

- G-Easy/Bebe Rexha: Me, Myself and I

Granted, not one of these songs is a sonnet but they do provide you with a way to get the feel of the iambic pentameter and different ways it can be used.

If you wanted to see popular songs in sonnet form... some ingenious and creative soul has taken lyrics from the likes of Beyoncé and The Backstreet Boys and turned them into sonnets!

2. Master the Iambic Pentameter

Internalising the iambic ‘beat’ is no chore; you could practice it while walking – left foot unstressed/right foot stressed, by clapping your hands (soft-LOUD soft-LOUD), drumming your fingers... any type of rhythmic activity.

Mastering the iambic pentameter is vital to writing a sonnet with proper flow.

Once you have found a topic to write about and internalised the iambic beat, writing a sonnet is a breeze!

Remember that the first quatrain introduces the situation and, at least as far as Shakespearian sonnets are concerned, follows an ABAB pattern – meaning that the third line should rhyme with the first and the fourth with the second.

Here is an example of just such a quatrain:

Ago, I saw you walking fair one day

Though fear forbade my presence should come near.

Froze, the words that I could never say

Though in my heart remain so very dear.

Does it meet all of the criteria for a proper iambic pentameter quatrain and the opening verse of a sonnet? Let’s see:

- Each line contains five iambic feet (in other words, five duh-DUMs).

- Line three rhymes with line one and line four rhymes with line two.

- It outlines a situation (we wonder why the speaker fears approaching and what s/he wanted to say)

3. Play with Words.

You’ll note that there are several words in this stanza that generally would not be used in normal conversation, at least not in the form or in the place they are used here.

Poetic license gives you permission to convey meaning by bending common language rules and expanding word meanings.

Our great bard Shakespeare was famous for perverting the meaning of words; his frequent use of anon is the perfect example of such.

The word anon dates back to 12th century English. Its original meaning was straightaway, or forthwith. Through Shakespeare’s persistent misuse of this word, it has come to mean the exact opposite: soon, or in a while.

We can see why he loved that word: it is compact and convenient, subjecting itself neatly and repeatedly to the iambic pentameter. And it’s easy to rhyme!

Make Ample Use of Poetic License – so long as you don’t completely vandalise the language!

Poetic license permits the use of froze instead of frozen to describe those unuttered words. Doing so even lends urgency to the situation by implying the words froze upon the sight of the person in question.

4. Depict a Complete Scene in 14 Lines.

To do that properly and effectively, you should use as many words and phrases that would call up visual imagery as you can.

The phrase ‘fear forbade my presence to come near’ conveys so much more than ‘I had an anxiety attack and couldn’t approach you’, even though they represent essentially the same concept, right?

This stanza causes us to see fear as a looming, frightening, domineering entity denying the speaker the privilege of approaching the person in question. By contrast, ‘anxiety attack’ sounds paltry, doesn’t it?

The Quatrain

Our first quatrain has us off to a great start! We have the right number of feet and the right rhyming pattern; we have visual language that has outlined a situation. Now it is time for quatrain #2:

Delight in how the sun kisses your cheek;

Tortu’r in how I wish that it were me!

Mere audience with you is what I seek

As though your heart were once again trusting.

Also, there is an escalating use of poetic license. In fact, the more ardent the situation becomes the more license is given to express it all!

Find Out More about Different Poetic Forms

The benefit of poetry is that there are lots of different styles once you have tried sonnets poems. Give the other styles try, Limericks are light-hearted poems, historically Japanese Haiku poetry is traditional, to show a feeling an Epic style poem would work well, Adding music? then the Ballad poetry style is for you, If you are looking for a show of Friday night visit a slam poetry show or listen to free verse poetry style. So many kinds of poetry, meaning you will find your best style of poetry.

Summarise with AI:

very interesting and good article