For the past few years, elections around the world have been contentious affairs. Pressing social issues such as climate change and mass migrations, people fleeing violence in their home countries or the blight of drought and famine (and war!); racially charged incidents and religious persecution have all led to social unrest across the globe.

In many countries, strikes, protests and demonstrations achieve only minimal results. In nations whose citizens have the right to vote, the ballot box is where their voices are best heard.

2022 Elections in Hungary

Under Viktor Orban's leadership, Hungarian politics have turned towards authoritarianism, a progression that a substantial part of the population - mostly younger voters, stand against. The flip side of that coin is represented by a segment of the Hungarian population that believes their country is becoming far too liberal, even under Orban's strong authoritarian rule.

Two new political factions entered the fray, just in time for this year's elections.

For the first time since those parties' formation in 2018, the Everybody's Hungary movement and Our Homeland, the right-wing political party, claimed seats in that country's parliamentary elections. However, Viktor Orban's Fidesz party retained the majority, claiming 52% of the votes.

2022 Elections in the Philippines

In 1965, Ferdinand Marcos was elected president; he served for 21 years. During that time, he and his wife, Imelda unabashedly plundered. Their actions were particularly offensive considering that, while Mrs Marcos was commissioning grand palaces and going on shopping sprees abroad, their citizens were struggling through profound economic hardship and living under martial law.

The People Power Revolution (1986) forced Marcos out of power; they fled the country with as much of their loot as they could carry. Their plunder, estimated in the billions of dollars, earned them a Guinness Book entry for the 'Greatest Robbery of a Government'. Of the estimated $10 billion (top figure) they pocketed, only about a third has been recovered.

With this recent history in mind, how could it be that the Marcos' only son could even stand for election, let alone win?

Win, he did, though, with no concession or admission of guilt on his parents' behalf, and certainly with no apology or promise of restitution. Indeed, he's accused of whitewashing his family history and, just days after the election, he was chided for propagating a lie about being Oxford-educated.

Between his mother currently battling corruption charges and his fabrications - and with a warrant out for his arrest in the US, can Filipinos hope for any integrity in government with Bongbong at the helm?

Perhaps there's hope; protests over his electoral win are ongoing.

2022 Elections in France

Marine Le Pen represents France's far-right political party; they've been seeking power since the party's founding in 1972. Yet, somehow, despite a long history in politics, Marine never quite seems to hit the mark. That looked set to change during the 2022 presidential elections.

Throughout the campaign season, election pundits contended that it was anyone's race. Macron was a known and unpopular candidate and Le Pen had substantial support from constituencies that wanted to engineer their country's Frexit. The third contender in the race, Jean-Luc Mélanchon, ran neck-and-neck with those top two contenders despite a far smaller constituency.

France's presidential elections this year reflect voting patterns seen elsewhere in the world.

First, President Macron claimed the majority of votes not because he is well-liked and admired but because the public believes a Le Pen presidency would be untenable at best, and lead to the country's ruin, at worst. Second, the runoff election saw the lowest turnout of any since 1969.

These two factors, voter apathy and voting against a candidate (rather than for them) are two, relatively recent and profoundly impactful voting trends seen everywhere that citizens are allowed to vote.

How do the UK's 2022 elections stack up against these political flashpoints? Superprof conducts that analysis now.

2021 Elections in the UK

To understand the full import of this year's local elections, we have to go back one year.

You might call the 2021 local elections a double event because, thanks to COVID, no elections were held in 2020. Councils, unitary authorities and boroughs that typically elect 1/3 of their counsellors during the first three years of their four-year election cycle were not afforded the chance to bring in new blood while the countries were under lockdown orders.

Thus, the 2021 election became a frenzied affair. Campaign windows were not extended so voters were not afforded extra time to consider all of the candidates on their ballots. Furthermore, there was substantial confusion over how candidates could campaign.

Traditional methods such as door-knocking, leafletting and hosting public events were deemed too risky; only late in the campaign season did the government relent and allow candidates and their proxies to canvass and leaflet. But only so long as they observed social distancing rules and kept their face masks on.

The coronavirus pandemic precipitated a shift in political winds. As people started feeling the economic pinches and the hardship of trying to educate their kids at home while themselves trying to work, the national mood started to sour. It is precisely those elements of difficulty - those immediate concerns that led to low voter turnout and voters not caring about the issues candidates supported.

The winds of change the pandemic blew in wouldn't be felt until the 2022 elections. That's when the tide turned and England saw its greatest political upheaval in decades.

Local Elections in England

In the preceding segment, we mentioned that 1/3 of any voting district's counsellors stand for election in every voting year. That sounds a bit confusing unless you know the logic behind it.

Let's say a unitary authority - a name given to a voting district that has 100 members in its government. Each counsellor's arrival is staggered across three years, meaning that voters select only 1/3 of their government representatives in any election year. This gives novice politicians the chance to work with more seasoned veterans who can help them understand government processes and inner workings.

Election cycles last four years. For the first three years, voters decide on one-third of their governing body's candidates and/or party that best represents their political desires. In the fourth year, no local elections are held in that district.

Now, things get more confusing.

- Some districts'/regions' require half of their politicians to stand for election in each election year, instead of 1/3 of them. Each election cycle lasts for four years; thus, voters only need to vote twice per election cycle.

- Other districts vote in the entire body at once but these districts still uphold the 4-year election cycle.

- General elections: voting for Parliament representatives happens every five years

- In some districts across England, voters will choose their mayors via the supplementary vote system, meaning that each voter may select a primary and secondary candidate.

- The London mayor is also selected by the supplementary vote system

- The London Assembly, the 25-member body that oversees mayoral decisions are voted in via the 2-vote Additional Member system.

All of these voting systems, voting schedules and election cycles... why can't there be a unified system of voting across England? Or, for that matter, across the UK?

You need to read our companion article to find out.

Summary of the 2022 Elections

The previous segment only detailed elections in England. Now, let's talk about the other countries that make up the UK.

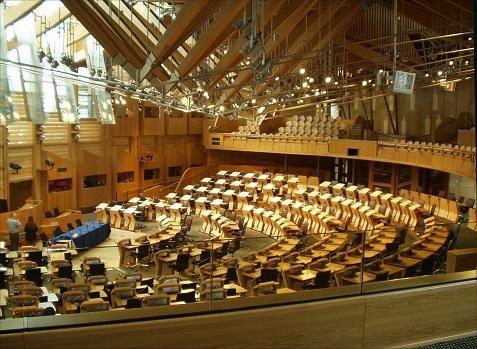

The Scottish and Welsh Parliament bodies are elected every five years. In Wales, the Senedd comprises 60 members drawn from five electoral regions. In Scotland, Parliament seats 129 members drawn from eight electoral regions. Each election offers voters two choices; one for their local candidate and the other for the party that will represent their region in Parliament.

Like the other UK Parliament votes, Northern Ireland votes for their new Assembly members every five years. Each of the country's 18 constituencies permits five Members of the Legislative Assembly, for a total of 90 members.

Beyond Parliamentary elections, these three countries also hold local elections, often on the same schedule as England's elections.

How did the 2022 elections turn out?

Across the UK, the Conservatives suffered heavy losses while liberal Democrats and the Labour Party showed significant gains. That shift doesn't represent a major change for Wales, a country that has always had a strong Labour presence. However, Plaid Cymru stands out as a winner for gaining control of four authorities. The rest of Wales' 22 councils have no majority representation.

Oh, and the Tories have none, either, after losing Monmouthshire, their lone stronghold.

In Scotland, the Scottish National Party (SNP) claimed 22 more seats for a whopping total of 453 counsellors. Here, too, the Conservatives lost big; a stunning downfall from the last election, when they held the second-highest number of seats. How can a party recover from losing 60 counsellors?

Sinn Féin seized the say in Northern Ireland, claiming 29% of the first-preference votes, giving them the largest slice of representation in Stormont. The runner-up party, the Democratic Unionists, claimed just over 21% of the vote. In this country, Conservative losses made no impact as they have no presence in government there.

Are you looking for more than a summary of the UK's 2022 election results?

Summarise with AI: