Chapters

At the dawn of the 16th century, the Catholic church was a force to be reckoned with, wielding immense power and influence across almost the entirety of Europe. From the grandest cathedral to the humblest parish church, the influence of the Church touched almost every aspect of daily life and society.

However, beneath the surface of this seemingly unshakable power, tensions and criticisms were beginning to brew that would soon erupt into the Protestant Reformation.

In this article, part of a series covering the events of the reformation of Europe, we’ll take a journey into the complex and often turbulent world of the Catholic Church in the years leading up to the Reformation, from 1500 to 1517.

Why Was the Catholic Church So Powerful during this Era?

The Catholic Church's power went beyond just religious matters and had a big influence on the regular day-to-day life of both peasants and nobles alike. It was very much a hierarchy, with the Pope at the top, and parish priests, bishops, cardinals, and other religious figures below him.

The Church also operated its own court system which was separate from those of the King's courts. This judicial power and the Church's influence on government made it a formidable force.

For example, not only were Monarchs expected to obey papal decrees, but the clergy enjoyed special legal privileges and exemptions from taxation.

When it came to regular people like peasants, the church was an ever-present part of their daily life. The local parish usually sat at the heart of the community, with the priest in charge overseeing education, social welfare and moral guidance.

The Church was also incredibly wealthy, with monasteries controlling vast agricultural estates where both peasants and monks worked and lived. This wealth allowed the Church to construct magnificent cathedrals and commission intricate pieces of religious artwork throughout Europe, many of which still stand today.

What Was the Nature of the Church's Religious Power?

The Catholic Church also held an unparalleled position as the sole authority on spiritual matters during this time. Essentially, its doctrines and teachings were considered the absolute truth, and questioning them was pretty much unthinkable.

Most people also followed the seven sacraments, which were sacred rituals integral to a person's spiritual journey from birth to death. These sacraments included things like baptism, confirmation, Holy Communion, penance, anointing of the sick, holy orders (for priests), and matrimony.

They were performed by ordained priests and were seen as essential for attaining salvation and securing your own place in heaven. However, the church's teachings also stated that faith alone was not enough for salvation and that believers must lead a life of righteousness, avoiding sins and instead performing good deeds.

As a result, both peasants and the rich were firmly under the control of the church, looking to priests and other religious leaders for guidance for fear of being condemned to an eternity in the depths of hell.

What Criticisms Were Levelled Against the Church?

As the Renaissance unfolded, a growing number of critics across Europe began to express concerns about corruption and immorality within the Catholic Church.

The Renaissance was a cultural and intellectual movement in Europe from the 14th to 17th centuries, characterised by a revival of classical art, literature, and learning, and a focus on humanism and individualism.

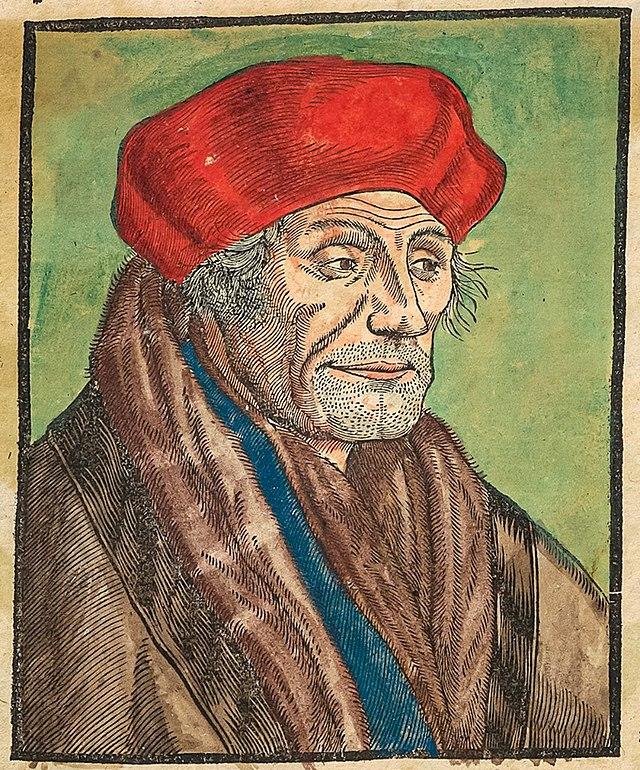

Chief among these detectors were the Christian Humanists, a group of religious scholars who wanted to see the Church return to its roots. This group included many notable figures like John Colet, an English theologian and dean of St Paul's cathedral, and Desiderius Erasmus, an extremely famous Dutch scholar and theologian.

Alongside their concerns about the church’s interpretation of the bible, the humanists were also critical of the lack of education and moral standards among the clergy as well. In their mind, the vast majority of priests and bishops and priests were more concerned with worldly matters like politics and personal wealth than with their actual spiritual duties.

The popes of this period were not free from criticism either. For example, Pope Alexander VI, who reigned from 1492 to 1503 was notorious for his corrupt practices, including simony (selling church offices), nepotism (favouring his relatives), and his involvement in important political and military affairs.

Despite this, most of the general public remained afraid to openly defy the Church's authority. Having witnessed the fate of groups like the Hussites, who were often brutally suppressed for their demands for reform, most people were all too aware of the grave risks challenging the Church would pose.

How Widespread Was the Demand for Reform?

By 1517, the calls for widespread reform had grown louder and ever more persistent. Why? Well, over time, the opinions of the Humanists had started to spread widely among the educated classes due to the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440.

The printing press revolutionised the spread of ideas during the Reformation by enabling the mass production and distribution of reformist texts, leading to a wider dissemination of critical and reformist views across Europe.

However, discontent was not just limited to intellectuals either. Both the nobility and common people were also becoming increasingly resentful of the church’s financial practices, especially the sale of indulgences which took advantage of people’s fear of damnation in order to make money.

Alongside this, there were also growing complaints about the Church's vast wealth and its unfair exemption from taxation. However, the demand for reform was not a popular opinion everywhere in Europe. For instance, those living in rural areas or who were amongst the lower class were largely unaware of the criticisms and remained committed to their faith and catholic practices.

Furthermore, while many scholars were in agreement that reform was necessary, there were significant disagreements on how to go about it. Moderate reformers, like Erasmus, wanted to see meaningful changes within the existing structure of the church but didn’t really question its religious teachings or its authority. On the other hand, radical reformers, like Martin Luther, were not afraid to heavily question many core catholic beliefs and campaign for a complete overhaul of religious authority.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Catholic Church in the early 16th century was an ever-present part of life for both nobles and common people alike. A rich and powerful institution, the church owned many farms across Europe and was not afraid to openly flaunt its wealth. Due to this, it faced growing discontent and calls for reform due to corruption, ignorance, and financial abuses from humanists and other critics.

While the demand for change varied among its critics, it was clear that the church was slowly but surely heading towards a crisis. The protestant reformation was just on the horizon, an event which would permanently split Western Christianity and change Europe’s religious landscape forever.

Summarise with AI: